Many food and agribusiness companies across the value chain are reassessing their strategies in light of significant ongoing industry shifts. Among these shifts, changing consumer preferences now require the food distribution chain to deliver healthier and more environmentally friendly products; advances in technology provide stakeholders with access to unprecedented volumes of information; consolidation at multiple levels is changing the competitive landscape as well as supplier-customer relationships; production innovations allow food to be grown in new ways; and capital from new investors is enabling a startup scene in the industry. However, simply adjusting a strategy to address the evolving environment will not be enough to succeed. Success also requires effectively implementing that new strategy.

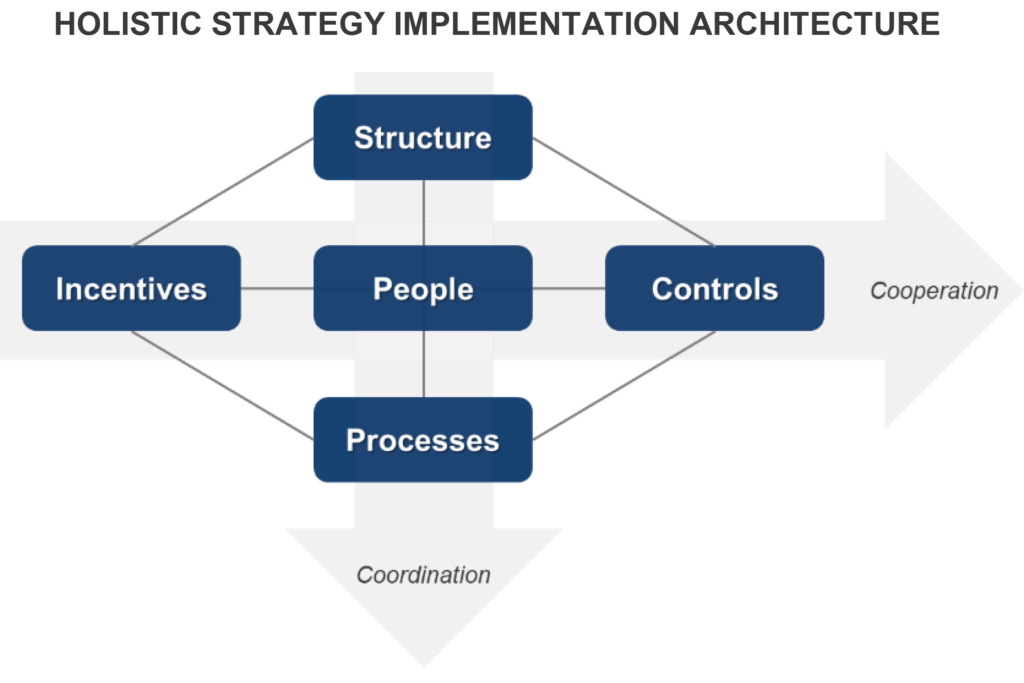

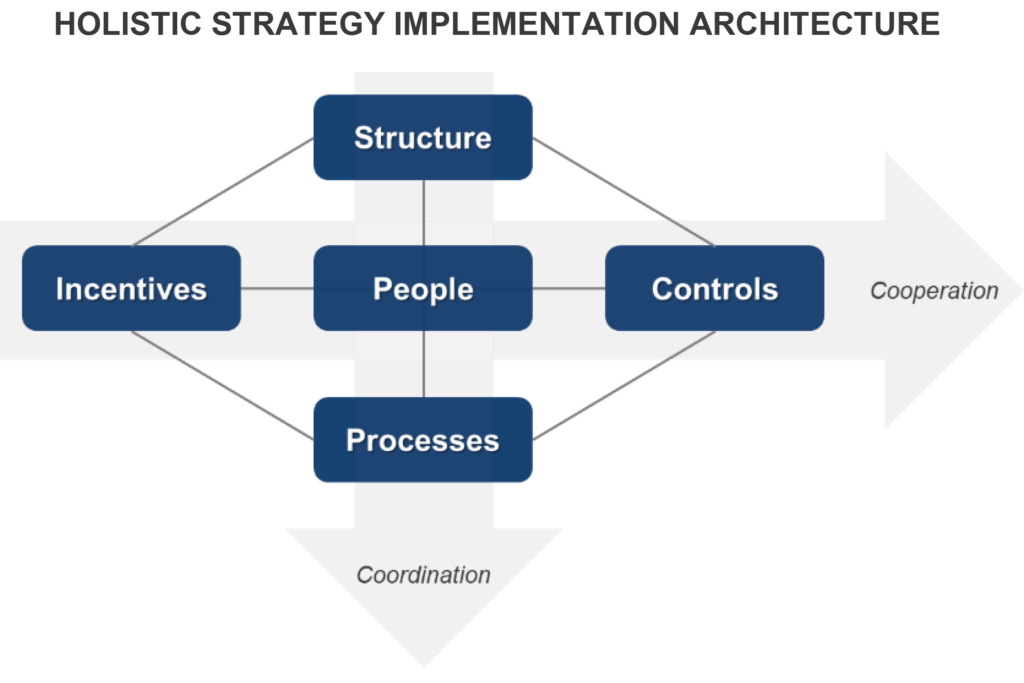

Most leaders realize that good results call for both a good strategy AND good strategy implementation. Unfortunately, all too often implementation planning is too narrow in focus, targeted at just one or two of a large set of decisions that must be made. Without proper attention paid to a holistic set of organizational elements, a good strategy may still fail.

Peter Johnson, executive in residence at the Fuqua School of Business at Duke University, describes successful strategy implementation as involving both effective coordination and cooperation.

Coordination is the process of aligning activities across an organization. Leaders must decide what degree of coordination between individuals, teams, and businesses will be optimal for the company and its strategy. They must decide how work will flow, what will be shared between businesses, how sharing will occur, who is responsible for resources, where will decision rights reside, etc. The following elements are the levers that can be used to manipulate coordination:

Structure – The way in which the work done by the company is arranged. Will activity be organized by function, by product line, or by geography? Will work be centralized or decentralized? What does the reporting hierarchy look like? How is the senior team composed? An aligned structure ensures the proper teams will be in place to adequately execute the strategy. For example, Airbnb organizes into small geographic teams with high levels of collaboration with global functions to enable local responsiveness while maintaining efficiency.

Processes – The way in which activities are integrated. This element includes how decisions are made, what interfaces are in place between business units or functions, how information flows, how resources are shared, and how work progresses from one stage to another. Without well thought-out processes, strategic objectives may stall. For example, UPS manages all its businesses (air, ground, domestic, international, commercial, residential) through a single pickup and delivery network. The single network process allows UPS to maximize network efficiency and asset utilization.

Cooperation is the process of aligning individuals to behave in the organization’s best interest. In other words, this is how companies influence team members to work according to the new strategy. The following elements are the levers that can be used to increase cooperation:

Controls – Metrics that appropriately measure performance and enable leaders to ascertain how effectively the strategy is being applied and, if necessary, what changes need to be made. Choosing the correct metrics requires clearly understanding the objectives. Metrics can be highly varied, based on individual vs. group achievement, outcomes vs. behaviors, numbers vs. ratings vs. observations. Effective controls allow leaders to determine how to support, reinforce, or improve the strategy. For example, the Oakland Athletics (of Moneyball fame) discarded the common practice of measuring baseball players’ abilities to run, throw, field, and hit and instead used on-base percentage metrics to recruit winning players more economically.

Incentives – Tools used to motivate cooperative behavior, including both extrinsic motivators (pay and bonuses) and intrinsic motivators (recognition, autonomy, purpose). With proper incentives, team members can effectively help drive a strategy forward. For example, employees at Southwest Airlines can give gratitude points to each other. This practice supports a community culture among employees, which encourages them to contribute to the strategy of making flying a fun, positive experience for customers.

Finally, one critical organizational element impacts both coordination and cooperation:

People – The talent in an organization’s workforce. Leaders must decide what knowledge, skills, and experiences are needed in which positions to successfully integrate the strategy. This may involve hiring new people, moving people to new jobs, ensuring the right mix of attributes on a team, and creating a plan for people development. Having the right people in place can make or break a strategy. For example, in order to meet the economic imperatives it faced in 2014, TheNew York Times took the unusual step of appointing a business executive, rather than someone in its news organization, to an assistant managing editor role.

Kristina Rose, a consultant with The Context Network, notes that the appropriate approach to strategy implementation will depend on a company’s current organization, resources, and portfolio. “But in all cases,” she says, “it is critical to consider the holistic set of elements that will impact the results of the strategy.” Too many leaders focus most of their attention exclusively on structural or incentive levers, when the reality is that successful implementation involves a complex, interwoven web of decisions. The complete architecture created from those decisions must be “clear (understandable across the organization), coherent (all elements fit together in a supportive and reinforcing manner), and relevant (aligned with the strategic objective)” (Johnson). If the levers are aligned correctly, an organization will get the performance desired from its strategy.

Successfully launching a strategy depends on an array of interwoven elements and decisions, just as launching a plane depends on a whole system of maintenance engineers, fuel availability, national and sometimes international airspace regulations, a customer reservation system, a maintained airstrip, and many more factors.

Of course, any shift in strategy requires a simultaneous updating of this system of levers to ensure it services the new strategy appropriately. This holds true during times of planned strategy revamps, growth of the firm over time, expansion of strategy to new geographies, expansion of business portfolio, strategic transformation, etc.

The Context Network, with its broad array of consulting, business, and subject-matter experts, has deep experience with helping clients plan their strategy implementation in a systematic, impactful way. For more information about Context’s implementation support, contact Principal Tray Thomas at tray.thomas@contextnet.com.

Sources:

Engineering Culture at Airbnb, nerds.airbnb.com

UPS vs. FedEx: Comparing Business Models and Strategies, Investopedia

The True Measures of Success, Harvard Business Review

Southwestaircommunity.com

An Unusual Hire, for Uncommon Times, nytimes.com

Long-Term Economic Impacts:

Long-Term Economic Impacts:  Environmental Impacts:

Environmental Impacts:  Social Impacts

Social Impacts

Risk mitigation can also come in the form of financial decision-making. For many in agriculture and raw material sectors, price transparency from the futures market provides an expectation-setting experience for everyone involved. The producers rely on the futures market to make production decisions, end-use customers rely on it to make purchasing decisions. Could market transparency lead to more informed decision making across the entire supply chain? Could it assist all parties including consumers in the long-term?

Risk mitigation can also come in the form of financial decision-making. For many in agriculture and raw material sectors, price transparency from the futures market provides an expectation-setting experience for everyone involved. The producers rely on the futures market to make production decisions, end-use customers rely on it to make purchasing decisions. Could market transparency lead to more informed decision making across the entire supply chain? Could it assist all parties including consumers in the long-term?

Gobbee, who is based in Buenos Aires, Argentina, ties the activities of SWFs in South America to strategic policies emphasizing food security in countries like Saudi Arabia and China. He notes, “Sovereign wealth funds are acting to ensure their countries have access to the resources they’ll need in the future. Recognizing their dependence on food imports, they’re seeking to gain more control of food value chain.”

Gobbee, who is based in Buenos Aires, Argentina, ties the activities of SWFs in South America to strategic policies emphasizing food security in countries like Saudi Arabia and China. He notes, “Sovereign wealth funds are acting to ensure their countries have access to the resources they’ll need in the future. Recognizing their dependence on food imports, they’re seeking to gain more control of food value chain.”

Globally, investment in agriculture as an alternate asset category has multiplied fourfold in just 12 years (see Figure 1), with investments in South America second only to North America. And this appears to be just the beginning. Agriculture is still a 3% of the 6.6 trillion that the alternative assets category accounts for. Global ag investments are projected to triple by 2030 according to research conducted by investment analyst GOAGRO in coordination with the Centro de Agronegocios y Alimentos of Austral University.

Globally, investment in agriculture as an alternate asset category has multiplied fourfold in just 12 years (see Figure 1), with investments in South America second only to North America. And this appears to be just the beginning. Agriculture is still a 3% of the 6.6 trillion that the alternative assets category accounts for. Global ag investments are projected to triple by 2030 according to research conducted by investment analyst GOAGRO in coordination with the Centro de Agronegocios y Alimentos of Austral University. The third driver of agricultural investment in the region reflects a heightened recognition that South America is well positioned to satisfy rising global demand for food, which of course ties into the other two drivers.

The third driver of agricultural investment in the region reflects a heightened recognition that South America is well positioned to satisfy rising global demand for food, which of course ties into the other two drivers.